On this page

- Artificial intelligence

-

Public Service Delivery

- The APS will need to do more with less to meet community expectations of public services in the future

- Drivers of change

- Box 3: Australia’s demographic changes

- Government agencies have already used automation to deliver better outcomes for users

- There are also opportunities to use AI for public service delivery

- The state of trust in the public service’s use of AI

Artificial intelligence

Artificial intelligence is rapidly evolving

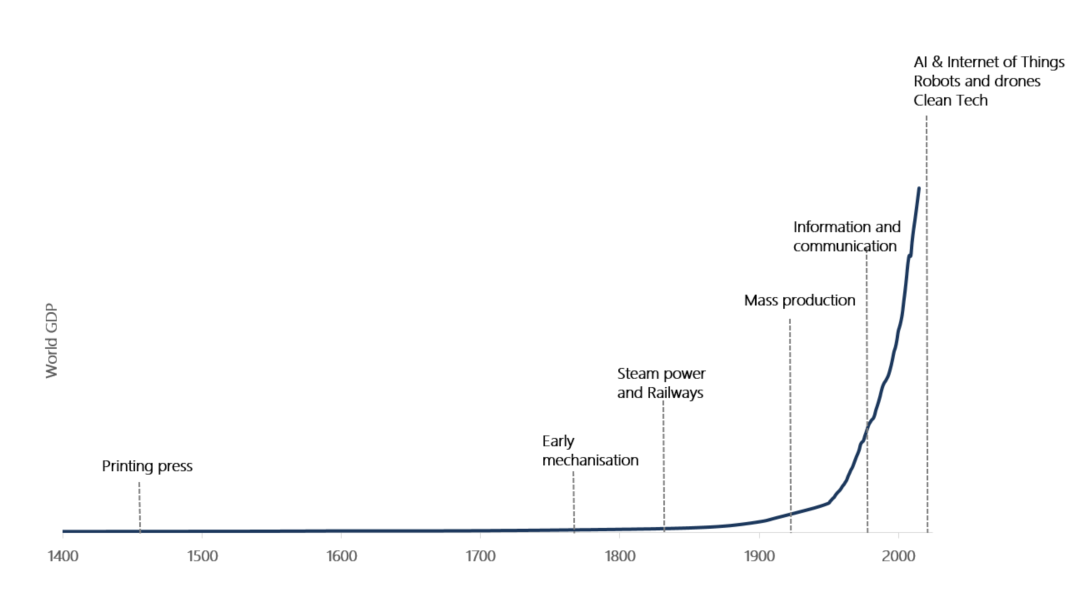

Technological innovations have driven world GDP growth over the past millennium, and with each wave of technological advancement, the way humans live, work and relate to each other has changed (Figure 2). This trend will continue with AI.

Indeed, the pace of change in AI has been substantial. In just five years, AI and its capabilities have undergone a rapid evolution – from experimental applications to AI solutions and applications that are widely adopted and used across society. This has been fuelled by an increase in computing power, investment and consumer demand. AI is expected to be worth $22.17 trillion to the global economy by 2030.[11] For Australia, digital innovations including AI, could cumulatively contribute $315 billion to the Australian economy by 2030.[12]

Source: Based on Our World In Data, A long-term timeline of technology. Output of world economy overlaid with key technological advancements.

Drivers of change

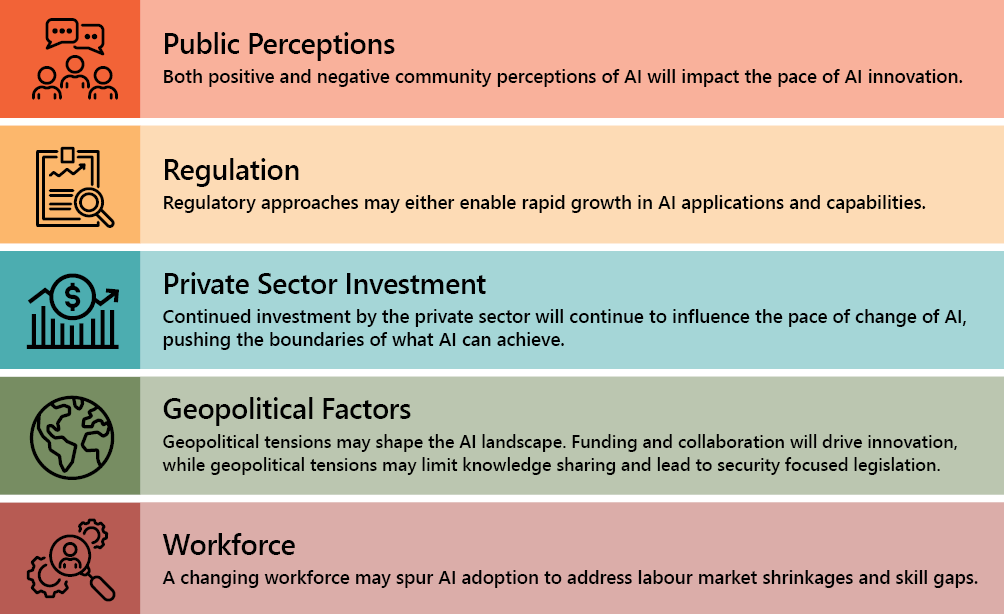

Given this rapid pace of change, experts caution against making predictions about the future potential of AI technologies.[13] Nevertheless, there are a number of factors that are likely to shape how AI is developed and used over the coming decade (Figure 3).

Public perceptions: Positive perceptions of AI may drive future developments in AI systems by influencing demand, investment and adoption of AI technologies in the public and private sectors, fostering innovation and growth in the field. Conversely, negative perceptions, such as concerns about data security and privacy issues, may prompt a slower pace of AI development, implementation and use (Box 2).

Regulation: Regulation, both domestic and international, may either enable a rapid change of pace with AI by providing confidence to investors, developers and users, or slow development, implementation and use of AI by introducing complexity, uncertainty and red tape. Innovation will be shaped by legislative requirements and regulation, and influenced by voluntary ethical standards and frameworks. In Australia, there is already considerable work underway in this space.[14] The borderless nature of the internet and digital platforms will challenge the effective enforcement of regulations and standards across jurisdictions.

Private sector investment and digital capitalism: The private sector will drive change in AI by investing in R&D, fostering innovation through start-ups and large technology companies, and deploying bespoke AI solutions that solve real-world problems. Platform-based, data-driven, and AI-powered businesses will become ever more central to economies and societies and data will increasingly emerge as a pivotal and core valuable resource. While this may lead to advancement in AI algorithms, hardware and data infrastructure, pushing the boundaries of what AI can currently achieve, it is also likely that a handful of corporations will become dominant market players. There is potential for this market power to significantly alter economic drivers for both consumers and competitors. Trust in use of data will become paramount, with any mishandling or unauthorised use of data eroding trust including in the AI systems that rely on such information.

Geopolitical factors: Geopolitical tensions may result in restrictions on the sharing of AI-related knowledge and technologies, affecting international collaboration. Further, large cyber security incidents in other jurisdictions may spill over into Australia’s digital environment, putting AI systems and tools at risk. As cyber threats become more sophisticated, the adoption and integration of AI‑driven cybersecurity measures are likely to increase to protect sensitive information and critical infrastructure.

Workforce: Labour and skills gaps globally are an important consideration for developing and maintaining AI solutions. Emerging skill requirements have resulted in demand and supply issues across a range of industries. Changing workforce needs, combined with labour force shrinkage overall will increase demand for automation and AI-powered solutions to improve efficiency and fill gaps left by labour shortages. The changing demographic landscape and workforce dynamics are likely to push the private sector toward greater AI integration to ensure sustained productivity and operational continuity. This, in turn, will drive innovation advancements in AI itself.

Box 2: Opportunities and risks of AI

Public perceptions of AI are likely to reflect awareness and understanding of the opportunities and risks of AI, including:

Opportunities

- Automation: AI-driven automation can increase efficiency by handling repetitive tasks, freeing up time for more creative and complex work.

- Healthcare advancements: AI can contribute to better diagnosis, treatment, remote health care opportunities, and drug discovery, potentially revolutionising healthcare.

- Enhanced decision making: AI’s data analysis capabilities can assist in making informed decisions across various industries.

- Improved customer experience: AI powered tools like chatbots can provide personalised customer support, enhancing user satisfaction.

- Efficient resource management: AI can optimise resource allocation.

Risks

- Bias and fairness: AI systems can inherit biases present in their training data, leading to unfair or discriminatory outcomes.

- Privacy concerns: The extensive collection and analysis of personal data for AI can raise privacy and security issues.

- Unintended consequences: Complex AI systems might behave unpredictably, causing unintended outcomes at scale that are hard to control.

- Dependency and reliability: Overreliance on AI could result in systems breaking down or causing disruptions when they fail.

- Inaccuracies: The outputs of AI models can be entirely erroneous, or simply misleading (known as hallucinations).

- Job displacement: AI could lead to a change in skills required, affecting employment opportunities for some.

Public Service Delivery

The APS will need to do more with less to meet community expectations of public services in the future

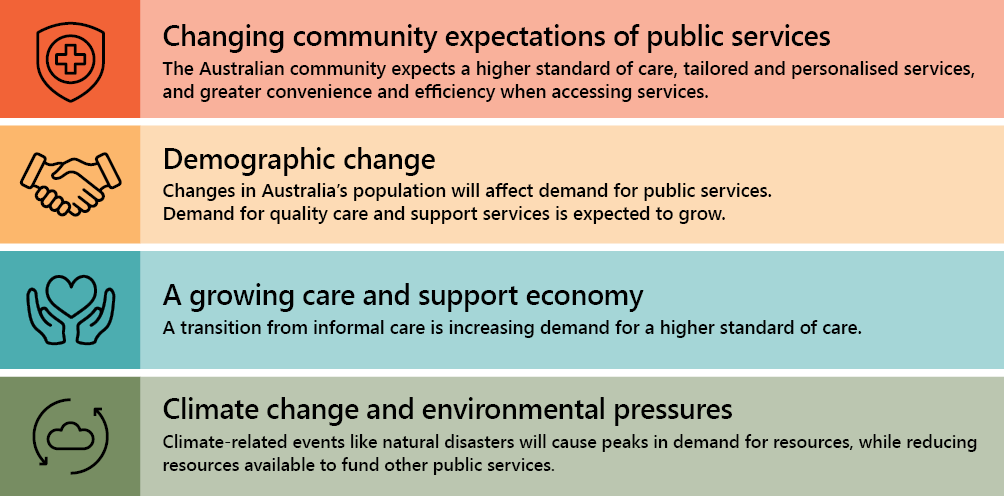

Public services in the future will be shaped by changing societal norms and heightened community expectations of government around the quality of services, particularly as Australia’s population ages. At the same time, external forces such as climate change are expected to increase demand for services while decreasing the resources (people and funding) available to provide them (Figure 4).

Drivers of change

Community expectations of public services: The Australian community’s expectations of public services are changing. Ongoing digital transformation is expected to continue to raise incomes and quality of life.[15] Expectations around the quality of services have increased. Many in the community expect greater responsiveness, convenience and efficiency when accessing services. For example, online platforms and streamlined processes continue to minimise wait times and enhance accessibility.

Demographic change: Changes in Australia’s population will affect demand for public services (Box 3). Australia’s population is ageing, and demand for quality care and support services is expected to grow as the share of older Australians in the population increases. Public services are expected to adapt by focussing on elder care, accessible health care options and tailored social programs, while still providing existing services. Increased immigration may require agencies to provide resources that cater to the specific requirements of immigrants. At the same time, an increase in the share of older Australians in the population will mean fewer working-age Australians to help fund more government services.

Box 3: Australia’s demographic changes

Population growth is projected to increase by 3.9 million people over the next 10 years to 2033.

In 2022–23, approximately 4.6 million people (17% of Australia’s total population), were aged 65 and over. In 2032–33 this is projected to increase to approximately 5.9 million people (19% of Australia’s total population).

The number and percentage of older Australians is expected to continue to grow. By 2062–63, it is projected that older people in Australia will make up 23% of the total population.[16]

A growing care and support economy: Social changes, including the steady expansion of women’s workforce participation have led to a shift away from unpaid care provision, towards formal care arrangements, including for children and ageing parents.[17] Expectations around the standard of care (how and where care is provided) have increased.

Climate change and environmental pressures: A warming climate and more frequent and intense natural disasters associated with climate change will affect the capacity of the APS to deliver public services. Demand for services will likely experience peaks in response to climate-related events that cause acute increases in community needs. Further, the resources needed to respond to climate impacts will likely draw resources from elsewhere in the public service.

Government agencies have already used automation to deliver better outcomes for users

Automated Decision Making (ADM) refers to the application of automation in any part of the decision-making process. It includes using automated systems to either:

- make the final decision

- make interim assessments or decisions leading up to the final decision

- refer to a human decision-maker where further information is required or an adverse decision is determined

- guide a human decision-maker through relevant facts, legislation or policy

- automate aspects of the fact-finding process which may influence an interim decision or the final decision.[18]

Currently, there are a number of ways that the public service can use automation to deliver tangible benefits such as efficiency. For example, Services Australia has applied automation technologies (not Artificial Intelligence) to process payments and deliver faster outcomes to Australians, so that they receive support when they need it most. Importantly, in those instances this happened in conjunction with Services Australia staff, not instead of staff, meaning that no one will have their claim refused through automation. Refusal decisions are made through manual processing by Services Australia staff.

There are also opportunities to use AI for public service delivery

AI capabilities are already being used in some Commonwealth government agencies.[19] For example the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) uses AI models to identify business activity statement lodgements with high-risk refunds prior to the refund issuing to taxpayers. This allows targeted treatment of risks such as identity crime, fraud and incorrect reporting. ATO staff will determine whether the refund can be issued based on currently held information, or further review is required. Where staff make a decision not to issue the refund, a taxpayer has the right to seek a review of the decision.

Some other ways that AI could be used in public service delivery now or in the near future include:

- Chatbots and virtual assistants: implementing AI powered chatbots on agency websites, communication channels, and for tasks such as claims processing can help agencies to provide citizens with quick responses to common inquiries and streamline customer service delivery.

- Data analysis and insights: AI can analyse large datasets to extract valuable insights for informed decision making.

- Automated data entry: AI can automate routine tasks, reducing administrative burden and minimising errors in data management.

- Language translation: AI-powered language translation tools can aid in providing multilingual services and facilitating communication with diverse populations.

- Fraud detection: AI can be used in document and image detection and recognition for border control, and for fraud detection in benefit applications.

- Minimise documentation errors: AI can check that customers or staff have submitted appropriate and error free documentation. This reduces duplication and speeds up processing times so as to improve service delivery.

- Automate claim processing: AI can reduce the time between requests for a government service and an outcome of that request being delivered. This is particularly relevant during times of emergency (e.g. the COVID Disaster Payment and Australian Government Disaster Relief Payment).

The state of trust in the public service’s use of AI

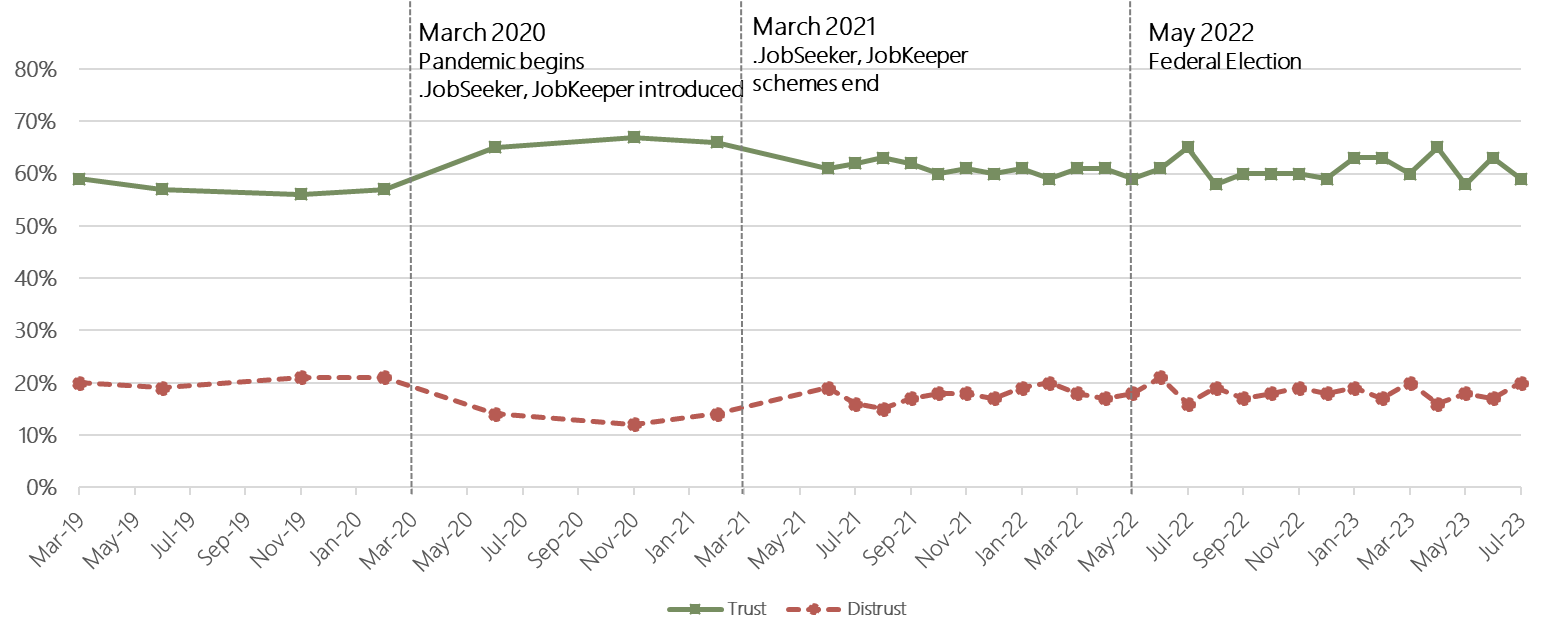

Currently, most people (61%) trust Australian public services and believe they will change to meet Australians’ needs in the future.[20] One way public services will change in the future is through the development and use of AI by the APS.

Drivers of trust in public services

Crises: Recent events provide an insight into how trust in public services is affected by government actions (Figure 5 and Figure 6). During the COVID-19 pandemic, trust in public services increased significantly following the introduction of COVID-19 support programs like the JobSeeker and JobKeeper schemes,[21] and the Pandemic Leave Disaster Payments.

Source: Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (2022), Trust in Australian public services: 2022 Annual Report.

Source: Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (2022), Trust in Australian public services: 2022 Annual Report.

On the other hand, the community’s response to the recent Robodebt scheme has demonstrated how poor policy design can undermine trust in government and public services,[22] specifically the social security system:

…Scandals such as Robodebt undermine my confidence in the public service and government.

While Robodebt calculations were completed via algorithmic decision making (ADM) rather than AI, for most people this distinction will be irrelevant. The community’s views on public agencies as trustworthy adopters and users of digital technologies, including AI, are likely to be shaped by the impacts of the Robodebt Scheme, and the government’s response to the findings of the Royal Commission report, for the foreseeable future.

Community’s views on the use of AI in public service delivery

Australians views and trust in AI systems are a starting point for understanding how using AI in public service delivery might affect trustworthiness.

Overall, trust in AI systems is low in Australia

A recent global study of trust in AI by the University of Queensland and KPMG (UQ/KPMG) found that trust in AI systems is low in Australia.[23] Less than half of Australians (44%) believe the benefits of AI outweigh the risks. The study also found that only 35% of Australians agree that institutional safeguards, like regulations and legislative frameworks, are adequate.[24] However, the study did find that trust in Australia of AI systems has increased over time as the public gains more awareness of AI and its use in common applications.

Knowledge and understanding of AI is low in Australia

A recent survey of Trust in Australian Democracy found that more than half of people (57%) reported having zero or slight knowledge of AI, while almost two thirds (63%) reported having zero or slight understanding of when AI is being used.[25]

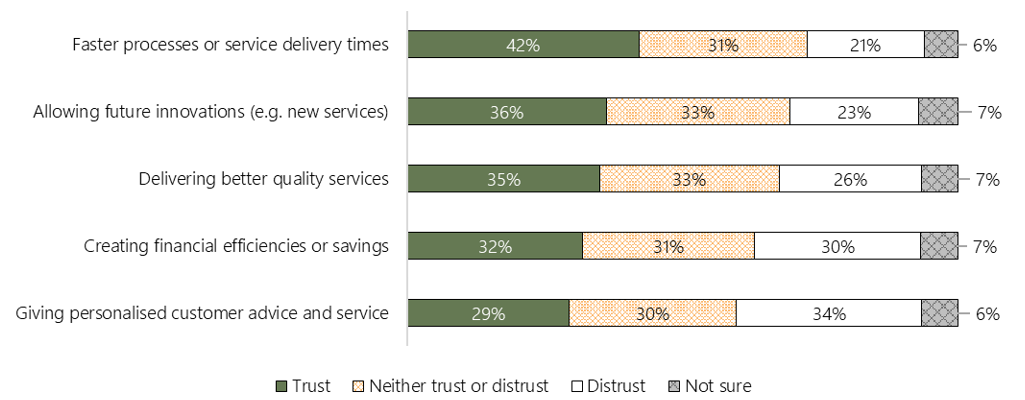

Trust in government’s ability to use AI in public service delivery varies by the purpose for which AI is being used

When choosing between a list of purposes for using AI, people reported highest trust in government’s ability to use AI to deliver services faster (42% of respondents). Over a third indicated that they trust government services to allow future innovations like creating new services. While personalisation is often discussed as one of the benefits that AI may offer for public service delivery, highest distrust was reported in government’s ability to use AI to provide personalised customer advice or services (34% distrust) (Figure 7). More than a third of respondents reported that they neither trust nor distrust government’s ability or were unsure.

Notes: Trust results show percentage of people who said they ‘trust’ or ‘strongly trust’ government agencies to responsibly use AI for the outlined purpose; Distrust results show percentage of people who said they ‘distrust’ or ‘strongly distrust’ government agencies to responsibly use AI for the outlined purpose

Source: Australian Public Service Commission, Survey of Trust in Australian Democracy (forthcoming)

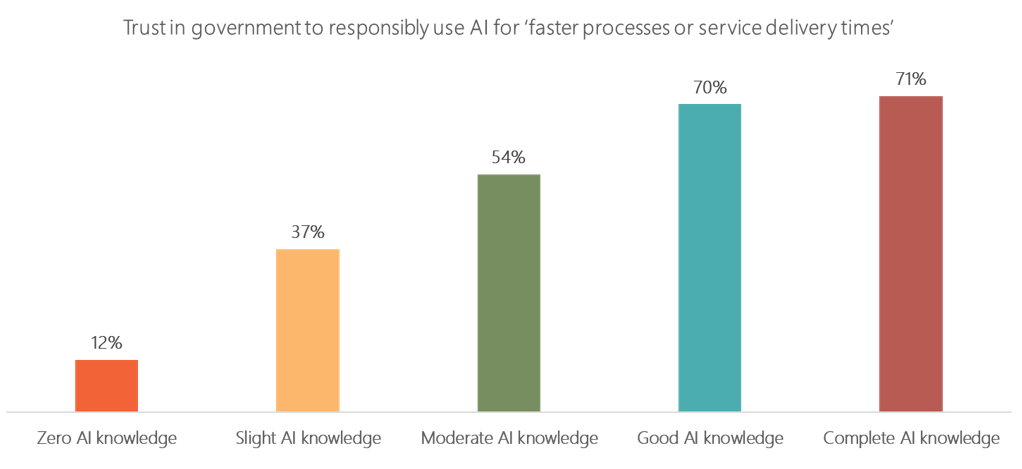

Higher knowledge of AI is associated with higher trust in government’s ability to use AI in public service delivery

Individuals who reported having higher knowledge of AI reported higher trust in government’s ability for any – or indeed, all – of the possible uses of AI. For example, 70% of people who reported knowing ‘very well’ about AI trust government to use AI to deliver faster services, compared with 54% who reported a moderate knowledge of AI, and 37% who reported having a slight knowledge of AI (Figure 8).

Notes: Results show percentage of people who said that they ‘trust’ or ‘strongly trust’ government agencies to responsibly use AI for providing ‘faster processes or service delivery times”. Results are cut by respondents’ self-reported knowledge of AI from the options ‘Not at all’, ‘Slightly’, ‘Moderately well’, ‘Very well’, and ‘Completely’.

Source: Australian Public Service Commission, Survey of Trust in Australian Democracy (forthcoming)

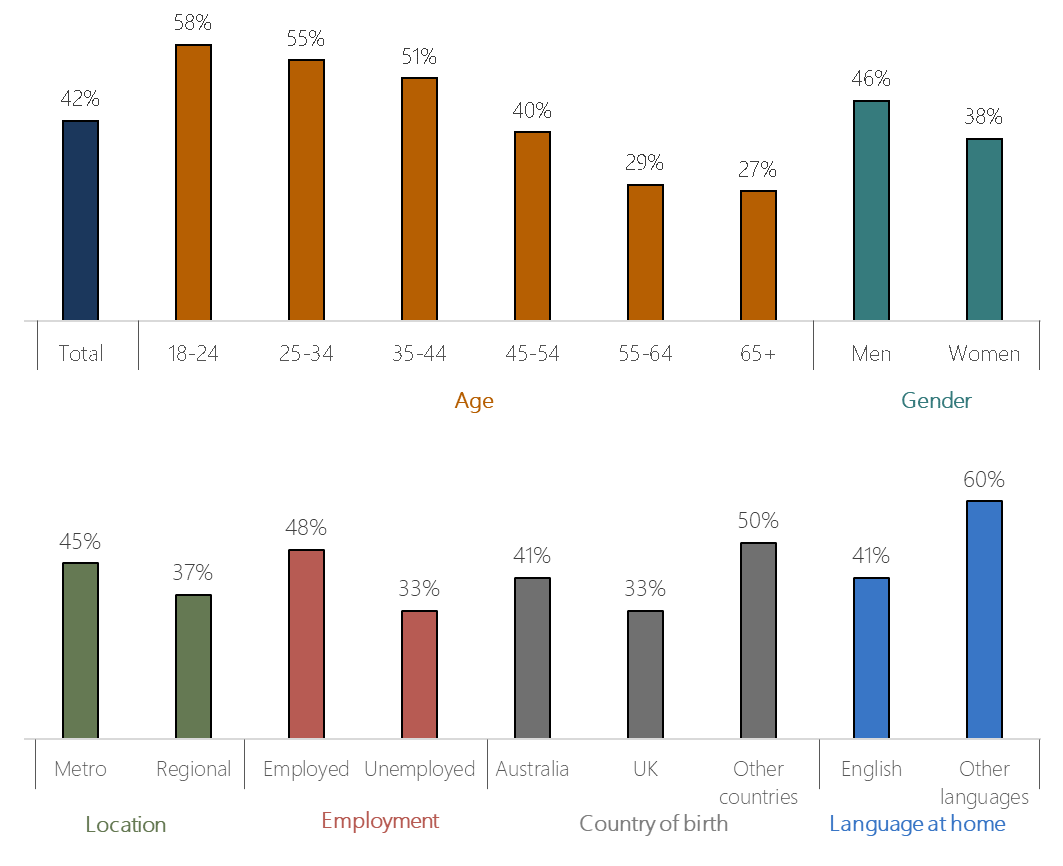

Trust in government’s ability to use AI varies across cohorts

Trust in government’s use of AI in public service delivery is shaped by social, cultural, economic and generational factors (Figure 9). For example:

- Younger people reported higher trust in government’s use of AI than older people.

- Women reported lower trust in government’s use of AI than men.

- People in regional Australia reported lower trust in government’s use of AI than those in metro areas.

- People born in Australia reported lower trust in government’s use of AI than those born overseas (with the exception of those born in the United Kingdom).

- People who speak English at home reported lower trust in government’s use of AI than those who speak a language other than English at home.

Source: Australian Public Service Commission, Survey of Trust in Australian Democracy (forthcoming)

To some extent, this may reflect different cohorts’ experiences with public services and (self-reported) knowledge of AI. For example, women and people in regional areas trust public services significantly less than men and people in metro areas, respectively, even though their service satisfaction levels are similar.[26] Women and people in regional areas also reported having lower knowledge and understanding of AI and its applications.

In contrast, younger people (under 45) have higher trust in government’s use of AI in public service delivery, despite tending to have lower trust in public services than people aged 65 and over[27] – a trend seen in most OECD countries.[28] This likely reflects their higher reported knowledge and understanding of AI and its applications.

Back to top