The first Long-term Insights Briefing explores how the APS could integrate artificial intelligence (AI) into public service delivery in the future, and how this might affect the trustworthiness of public service delivery. This background paper summarises the stakeholder engagement undertaken for the first briefing. This included focus groups with community representatives; workshops with AI and service delivery experts from the APS, academia, private sector and industry; and a combined workshop with community representatives and experts that used scenarios to explore how AI might affect the trustworthiness of public service delivery in the future.

The Long-term Insights Briefings

On 13 October 2022, the Minister for the Public Service, the Hon Katy Gallagher, announced that the APS would commence Long-term Insights Briefings as a part of the Government’s APS Reform Agenda.

The Long-term Insights Briefings are an initiative under Priority Two of the APS Reform Agenda: An APS that puts people and business at the centre of policy and services. They will strengthen policy development and planning in the APS by:

- Bringing together and helping the APS to understand the evidence, context, trends and implications of long-term, strategic policy challenges.

- Building the capability and institutional knowledge of the APS for long-term thinking, and position the APS to support the public interest now and into the future, by understanding the long-term impacts of what the APS does.

The purpose of the briefings is not to make recommendations or predictions about what will happen in the future. Instead, they will provide a base to underpin future policy thinking and decision making on specific policy challenges that may affect Australia and the Australian community in the medium and long term. It is anticipated they will form part of the evidence base for policy and decision making.

The briefings will use stakeholder engagement, research and futures thinking to analyse significant, complex, longer-term and cross-cutting issues. Importantly, the briefings will be developed through a process of genuine engagement with the Australian community on issues affecting them, as well as with experts from the APS, academia, industry and the not-for-profit sector.

This background paper summarises the stakeholder engagement undertaken for the first Long-term Insights Briefing, on ‘How might artificial intelligence affect the trustworthiness of public service delivery’.

Back to topThe first Long-term Insights Briefing

The first Long-term Insights Briefing explored how the APS could integrate AI into public service delivery in the future, and how this might affect the trustworthiness of public service delivery. AI could potentially transform public service delivery in ways that deliver a better experience and outcomes for the whole community. However, implementing AI poorly – such as by failing to address known risks of the technology, or failing to understand and respond to the concerns of different cohorts in the community – could erode the trustworthiness of the public service. This could result in the APS and the community as a whole failing to capture the benefits of AI.

Back to topStakeholder engagement in the pilot briefing

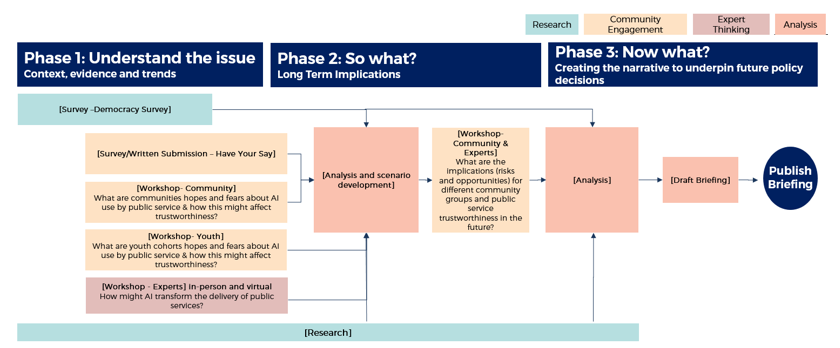

The briefing used community and expert engagement and futures thinking, together with research to explore how AI could transform public service delivery and the potential impacts of these changes on trustworthiness of service delivery agencies (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Phases and activities in the Long-term Insights Briefing pilot

Who were the pilot Long-term Insights Briefing stakeholders

Community engagement in the pilot briefing prioritised representatives from organisations representing women as well as not-for-profits that provide support to those experiencing vulnerabilities. While all Australians use public services, and most people trust Australian public services and believe they will change to meet Australians’ needs in the future, there are higher levels of distrust among (Figure 2):

- women

- people in regional areas

- First Nations people

- unemployed people

- people with disability.[1]

Figure 2. People who face marginalisation have higher levels of distrust in Australian public services

Source: Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (2022), Trust in Australian public services: Annual Report 2022, Trust in Australian public services: 2022 Annual Report.

AI and service delivery experts were consulted from a range of sectors, including the APS, academia, private sector and industry.

In total, stakeholder engagement encompassed:

- 91 people representing community, the APS, academia and industry, in workshops held in Phase 1 and Phase 2 (see Appendix A)

- 135 responses to a ‘Have your Say’ public consultation

- 5039 responses to the ‘Survey of Trust in Australian Democracy’ survey.

Survey results are available in a companion background paper.

What was the purpose of stakeholder engagement in the pilot Long-term Insights Briefing

Stakeholder engagement in the pilot briefing had two goals. Stakeholder engagement in Phase 1 explored the issue, the context, evidence and trends about AI use in public service delivery from the perspective of the community and AI and service delivery experts. Community engagement sought to understand the community’s hopes and fears about AI use in public service delivery; and their views on the attributes of public agencies that are important for trustworthiness. Community engagement also sought to understand community expectations of public services in the future, and how using AI in public service delivery could affect different cohorts in the community.

In Phase 1, the pilot briefing also engaged with AI and public service delivery experts from the APS, academia and industry to understand how AI could transform public service delivery in the future, and the key factors (trends and drivers) that will influence this. These workshops were facilitated by the Australian National University’s (ANU) National Security College Futures Hub.

Why use future scenarios in the Long-term Insights Briefing pilot?

The combined workshop with community representatives and AI and public service delivery experts in Phase 2 of the pilot briefing used scenarios to explore how AI might affect the trustworthiness of public service delivery in the future. The scenarios were possible, alternative futures for how the APS might integrate AI into public service delivery. Using the scenarios created an environment that encouraged community representatives to question and share their views on how the use of AI in the future might affect the trustworthiness of public service delivery, and further explore the range of issues identified in the community focus groups and expert workshops in Phase 1.

Back to topPhase 1: Community and expert workshops

What we heard: community focus groups

Participants were asked to share their perspectives on:

- what makes public services trustworthy for them

- AI and its use in public service delivery

- how AI might be used for their benefit in the future.

Participants emphasised that trust is enabled through 5 key elements:

- Integrity, which is demonstrated by protecting personal data and the privacy of individuals while providing information that can be trusted.

- Empathy, which is demonstrated by a public service that works for the good of the community as a whole and delivers services that are designed to support people.

- Competence and performance, which is demonstrated by public services that meet expectations and are user-friendly, and by having fit-for-purpose processes.

- Human elements of the system including human oversight and human interaction. There was a desire to talk to, be seen by, and receive the help from a real person who can empathise and offer services suited to an individual’s unique circumstances. There was a clear desire for human intervention and human oversight in decision making processes.

- Ongoing two-way relationships with the community, which can take a long time to build, change over time, and can be lost quickly. Trust is different for different cohorts of the community and cultural differences come into play. How communities have been treated in the past and in times of crisis will determine future interactions and perceptions of trustworthiness.

Participants identified a number of opportunities to use AI in public service delivery:

- Community members indicated that they saw opportunities around fast provision of information in “transaction” type services, where people want to get what they need without having to talk to a human.

- Community also saw opportunities to simplify bureaucratic processes, optimise resource allocations and reduce wait times by leveraging AI as a ‘sidekick’ for public services and public servants.

Participants also identified a number of risks from using AI in public service delivery:

- A risk that voices and personal data are stolen or used without permission, highlighting the importance of having government regulation in place and protecting the privacy and personal data of individuals.

- The risk of biased processes and outcomes, emphasising that “automation does not equal objectivity”; and the risk that the use of biased datasets and lack of diverse perspectives in design processes could result in unintentional biases and stereotypes being perpetuated.

- A lack of transparency in what information is being generated and how it’s being used.

- There was discomfort around a lack of human oversight with the use of AI, and a view that AI cannot make human-centred decisions and cannot understand wants or be empathetic.

- Concerns were raised around the loss of human interaction and that AI might create barriers to getting in touch with a real person in moments of need.

Participants also shared their views on what is needed to ensure trustworthy public service delivery:

- The quality of implementation. This could mean including diverse perspectives in the design process; recognising potential harms and stepping in early to address them; including a feedback loop; and critically analysing for unintentional biases that might creep in.

- There is a clear need for human-intervention points, especially in decision-making processes. AI can be used as a side-kick for efficiency, but there needs to be clear control points and stringent ethical guidance determining when humans step into and out of the loop.

- Cohorts and individuals in vulnerable situations need human interaction along with service provision. Ensuring provision of critical face-to-face interactions and human-centred systems is important in building trust with these cohorts. Participants suggested that culturally and trauma-informed AI doesn’t exist yet, but could make engaging with public services easier.

- While the trust base is low, familiarity with AI technology (and greater comfort with the technology) can have an overall positive affect on trust.

What we heard: expert workshops

AI and service delivery experts emphasised the need to prioritise key actions for Government today, to position the APS to respond to future transformations quickly and effectively:

- Legislation, regulation and ethics need to catch up to advances in technology. The people who are designing and implementing AI need access to the right tools, frameworks, guidelines and regulations. In public service delivery, AI development also needs to be guided by human impact management framework and ethics of service delivery.

- Workforce capability transformation. The speed of AI adoption will be determined by the speed of upskilling and reskilling the workforce. The National Skills Commission[2] prioritises computing and digital skills, including machine learning and artificial intelligence, among the fastest growing emerging skills in Australia. These skills are critical to respond to the digital world and the increasing use of digital technologies across the entire economy.

Participants identified a number of opportunities for Government to enhance trustworthiness of public service delivery through:

- Being open, clear and transparent around the adoption of AI, including proactive engagement and communication. This particularly relates to delays in terms of security, and upholding public service delivery principles.

- Development of technology needs to embed accountability and iterative monitoring for quality assurance, particularly in terms of data use. Participants noted that it would be important to identify who is responsible for AI decision making, and to ensure that human oversight is deployed effectively.

Participants also shared views on what needs to be considered and prioritised in design and development principles:

- The increasing inability to distinguish between human and AI interactions could undermine the integrity of data and IT security. There will be greater scope for fraud as individuals and service providers address verification challenges.

- Personalised and proactive services. There is demand for more intuitive and holistic approaches to service delivery, where push algorithms suggest services based on key life cycle stages.

- People should be able to opt in/opt out and choose the level of engagement with AI when accessing public services. It would be necessary to explore options for data sharing and ownership, particularly when opting in/out of services.

- There is concern around the perceived ‘black box’ of decision making shifting from human decision makers to automated AI decision making.

- Pace of adoption in service delivery will be accelerated by the private sector’s pace (of AI adoption and development) and could be constrained by the public service’s reliance on outdated data systems.

- There will be greater need and more frequent peaks in service delivery needs due to extreme events (natural disasters, weather etc). The APS will need to prepare to operate in an environment of unplanned large-scale disruption and be able to respond to the needs of citizens for unplanned or unanticipated support.

- AI could free up staff to handle high value and sensitive cases, and there will always be a continued need for human support officers/community advocates within public service delivery. This is critical in supporting society with ‘boots on the ground’, especially for individuals with complex needs.

- Generational differences need to be considered in terms of levels of knowledge about AI and technology adoption to prevent disparity in access to public services.

- Transformation of public service delivery needs to continue in order to provide greater and more flexible mobile delivery, particularly to regional and remote Australia. Face-to-face services will need to be offered in addition to digital services.

Phase 2: Futures scenario workshop

How were the future scenarios designed and analysed?

The alternative future scenarios for the pilot briefing were designed using a structured analytical process, supported by input from the ANU National Security College Futures Hub and experts from the APS. The process consisted of:

- Identifying drivers, trends and other factors that could shape future outcomes.

- Prioritising key drivers and factors, and how they might create potential outcomes over designated periods of time.

- Considering possible consequences of alternate future outcomes.

- Developing future scenarios, which organised linked elements (drivers, trends, factors and outcomes) into a future scenario.

The alternative future scenarios drew on the insights, issues and themes raised by participants in community focus groups and expert workshops held in Phase 1 of the pilot briefing. They were designed to emphasise issues, factors and attributes of agencies and public service delivery that were relevant to the briefing topic of How artificial intelligence might affect the trustworthiness of public service delivery. This included: integrity, performance, experience, empathy, vulnerability, privacy, discrimination, data bias, equality and fairness, and efficiency and efficacy. The four scenarios also intentionally had common features, such as the potential for bias that leads to discrimination; private sector involvement; and a reliance on the collection of personal data.

The scenarios were not designed to imply a prediction of the future or even to accurately reflect likely future outcomes. Instead, the future scenarios were designed to be provocative – ‘caricatures’ of possible future outcomes – in order to drive engagement and feedback from participants about the scenarios. This included what concerned or pleased them about the alternative future scenarios, and their sensitivities and priorities.

The four future scenarios were tested in combined workshops that included participants from community organisations representing societal segments. Each workshop group also included academics and experts in AI and data technologies, as well as APS members from service delivery agencies and related policy roles. Each scenario was tested with at least two separate groups. An iterative and duplicative approach to testing ensured the robustness of findings by comparing results across participants and groups, and by testing responses between narratives and context.

Future scenario 1: High personalisation and intervention

In 2026, after deep consultation with community and industry, the government embarked on a project to co-design Public Services 2.0. The aim was to integrate artificial intelligence with public services so that delivery is automatically calibrated to suit each persons’ needs. The goal was to provide an outcome situated between the two main models that had emerged in other countries: letting technology lead the way in the knowledge that there may be some ‘pain’ before the best model is identified; and the ultra-cautious model with the most minimal use of AI in the decision-making and delivery of public services.

The government initially promised a two year community consultation period, to engage with all elements of the community and with business. However, to ensure that all people were heard and all models tested with all people, the consultation process ballooned out to 5 years. By 2031, Australia had fallen about 5 years behind other developed nations in integrating AI with public service delivery. However, agreement was reached on a model with the commitment to continually engage with community and to manage emerging issues.

The new ServMe system of public service delivery provides a single point of access for all government services. Users will only ever need to open a single room on their personal holographic device (or webpage for those still using computers) to access government services and information. In this one room, they can do everything: from enrolling children in school, to getting a passport, to paying their taxes, to accessing the public health system. The government still operates by way of departments and agencies. However, they all tap into a single suit of AI technologies, which use centralised and standardised processes and protocols to access a single, constantly updating dataset, seamlessly providing a fully integrated public service.

Users are provided with choice on how they receive public services and which services they prefer to use:

NewYou is the top tier of service that a user can receive. A digital twin is created that acts and thinks like you. Trained on all the data it can be provided, this virtual you is able to act automatically in your interest, accessing services and benefits even the real you didn’t know were available.

To know what you need and are eligible for, the NewYou accesses extensive data from your phone, your wearable smart devices, search history, and even the devices of other uses that opt in to this level of service. The data collected provides information on things like your location, your calendar appointments and contacts, financial transactions, social media activity, heart rate and sleeping patterns, even your mental health and mood. With such detailed knowledge of you, the NewYou does all the work, so you never have to.

Users can opt in for personalised interventions, for example financial advice, health reports, employment opportunities, taxation responsibilities, and legal obligations.

Baseline is the lowest tier of service available, which uses the same level of data people would provide when purchasing a life insurance policy. This data is centralised, and options and responsibilities are forwarded to the device of the user’s choosing. If users prefer not to engage with government on a digital/holographic device, they can access shopfront services available in major cities.

Users can opt out whenever they wish to stop using a service and providing the relevant data. However, as the AI systems are constantly learning from data as it is received, models cannot “un‑learn” and the influence of your data will remain part of the system.

The High personalisation and intervention scenario sought to:

- Understand better the desire within community for a co-designed system of AI-enabled public service delivery, and a willingness to invest in such a process, provoking discussion around potential levels of community engagement and ongoing participation in processes of oversight and integrity assurance.

- Have participants describe their level of willingness to provide high levels of personal data for higher levels of personalisation of service delivery within an AI-enabled system.

- Harvest participant responses around the concept of differing levels of public service delivery, which is based on the amount of data individuals choose to share.

- Have participants consider the possible permanency of data in an AI model once it has been provided, to provoke discussion around the potential for discrimination based on levels of privacy, geographic location and desire for human-in-the-loop service delivery.

The scenario workshop identified that:

- How comfortable people are with sharing their data with government fundamentally depends on their individual circumstances.

- A highly personalised, fully integrated public service may bring benefits in certain situations, such as only having to tell your story to the government once. But, it may also come with risks in that a single point of access for services also becomes a single point of failure.

- People value the ability to be forgotten, the ability to correct data, and the ability to take context into account in decisions.

- A sensitivity to creating unique experiences and a loss of a shared understanding and awareness of what public services are and how they engage with and support the Australian public.

- There is a high likelihood that there will always be some – perhaps a significant share of people – that opt out of engaging with technological solutions and of providing more personal information to government.

Future scenario 2: Climate’s influence on the system

By 2033, severe weather events and natural disasters such as bushfires and droughts have become frequent and highly destructive. The changing environment heavily affects Australia. As the west deals with cyclones, the east suffers droughts and super-bushfires. Much of the nation’s public resources are taken up by trying to respond to events and to assisting communities in their recovery.

The bulk of human resources in the public sector have, over time, pivoted to supporting people traumatised or left destitute by events. Resources available for the development of new AI-enabled technologies are mostly dedicated to predicting and responding to natural disasters.

To make up for the shortfall in staff created by the need to respond to emergencies, AI-enabled digital technologies are now used to process routine and transactional public services. For the most part, this makes most interactions with the public service quick, efficient and predictable given the advances in AI technology since the early 2020s. There are well-established systems to automate most procedural tasks. Getting a passport, applying for unemployment benefits, lodging tax returns, licensing a business, receiving disability support, and similar processes can be managed from start to finish by AI applications.

To access these public services, people need to use a digital ID platform, with the most secure depending on bio-recognition, using either their voice, face or a breath-print that detects DNA. There is a growing criminal industry that uses AI applications to create fake bio-prints. However, this is difficult and only a small proportion of the population is ever bio-hacked. Those that lose control of their biodata have to revert to more traditional, manual approaches to accessing public services, while efforts to find a way to resecure these peoples’ bio-identities progress.

The majority of public services are seamless, efficient and effective, for those who provide reliable bio-credentials. To ensure fairness, there are options for those who choose a different type of digital ID or prefer to opt out of the digital systems altogether. They can still access public services by lodging an application to make an appointment to see a human. These applications are ranked in priority (victims of natural disasters are top priority, then acute health issues, then victims of criminal acts, then tax debts, and so on) and permission is granted to make an appointment with a human public servant as priorities are addressed. The wait can take some time, but all who apply are attended to, eventually.

The Climate’s influence on the system scenario sought to:

- Understand the willingness of people to access the majority of public services via AI-enabled digital platforms without engaging humans as part of the process, and gather insights on whether people are willing to trade potentially slower human-based service delivery for potentially faster AI-based service delivery.

- Understand the willingness of participants to use biometric data as a means for personal identification, and gain a response to a proposition that those who do not wish to share biometric data will not receive as prompt a service as those who share biometric data as a means for identification.

The scenario workshop identified that people:

- Understand the need to prioritise a response to those in crisis, but did not think that people who preferred to interact in person should receive a slower service.

- Are concerned about the level of service provided after a crisis and how local communities would be resourced for the longer-term work of rebuilding resilience in a community after an adverse event.

- Are very concerned about the use of personal data (and biometric data specifically), even in a crisis; and the impacts on those who would opt out of sharing their personal data altogether.

- Feel sympathy for those who might want to opt out of sharing personal data because of their experiences and concerns that their past history might discriminate against them.

- See a risk of a greater social divide for those who are experiencing complexity and vulnerability, and need ongoing public services through human engagement.

Future scenario 3: AI making public services healthy

By 2031, AI has improved many parts of daily life, such as by eliminating traffic congestion, reducing loneliness, and revolutionising manufacturing. To improve general health, the government brought together leading tech firms and a government research organisation to develop AI applications to track and manage people’s health at the level of the individual. The aim was to use AI to identify early signs of illness – physical and mental. This would facilitate faster intervention and quicker recovery, reducing illness in society and lowering the cost of public health.

Leveraging their expertise in healthy living and AI technology, the government research organisation engaged sports technology firms such as Fitbiz, Gramin and Poler, and contracted to partner with them on the new platform. Wearable devices, such as smart watches, shoes and clothing, were paired with smart beds, car seats and workstations to monitor people’s health and mood. Using this data, the AI applications provide early warning and advice to the user and the public health system when signs of potential illness arise. Hospitals and health clinics in city centres were linked to the network to help manage resourcing such as staff numbers, available beds, and even catering supplies in anticipation of workloads.

Over the few years the program has been operational, it has become clear that the gains will be immense. Data suggests that within a decade, illness and disease will be halved in cities and the spending on public health reduced by 60%. With the major hospitals needing less staff, government is developing a strategy to transfer doctors and nurses to outer suburban, regional and remote areas where health services remain responsive given that local infrastructure cannot support AI-enabled predictive networks.

With the savings made in public health, the government has also begun developing a plan to use models trained on the data from the city centres in outer-urban, regional and remote hospitals. This system will use the data from city centres to predict the kinds of illnesses needing treatment and where resources would need to be deployed in anticipation of the need to treat advanced illnesses.

In addition, it is common to hear calls in the media for those who choose not to provide their health data to be charged a premium for health services. Without early interventions, those who do not share data are ill more often and for longer, and use significantly more public resources as a consequence.

The AI making public services healthy scenario sought to:

- Test participant interest in highly personalised service delivery, to understand potential desire for personalised interventions (in this circumstance, for health benefits); and to provide an opportunity for participants to consider their willingness to provide high levels of highly personal data and biographic data to government agencies.

- Present a scenario where private industry was integrated into the delivery of public services, so that participants could consider the difference between sharing data with government and private industry.

- Present a situation where public service delivery differs based on access to digital infrastructure, driving discussion around disadvantage and biases in data collection and usage.

- Provoke discussion regarding how society should navigate a future where those who prefer not to disclose personal data for personalised delivery and early intervention potentially cause a higher drain on public budgets.

The scenario workshop identified that people:

- Are reluctant to share personal data with private industry, as their profit motive may encourage them to focus on the more profitable sectors of society; and are reluctant to share data that may travel beyond the jurisdiction of the Australian government.

- Are concerned that societal divides and inequalities may increase, based on demographic factors and comfort with sharing data; and that already marginalised groups could fall through the cracks.

- Are sensitive to the existence of disadvantage and discrimination in the way public services are delivered, regardless of whether it is happening to them or others.

- Are concerned that cohorts who lack trust in public services could be penalised further through reduced access to services; and that providing access to services based on acceptance of technological solutions is coercive.

- Believe that a reliance on impersonalised, automated and data-enabled services would further erode trust among First Nations communities (where trust is already low), and drive greater disengagement with government.

Future scenario 4: Public Private Partnerships

By 2028, the AI Revolution has influenced the way we go about our lives. Retail outlets identify you based on your digital wallet or biodata, and simply charge your bank account for what you take. Bank accounts monitor your income and spending patterns and notify you when significant outlays are expected or when you may be eligible for a public service based on your purchases (paediatricians fees, legal services or school enrolments, for example). Insurance companies are able to access your data, prefill forms and automatically personalise policies with precision, saving time and effort. The efficiencies gained with the introduction of AI leads to cheaper goods and services across the board.

Governments in Australia have not kept up with industry. Legacy systems, privacy regulations and having to keep to a higher standard – ensuring that all automated processes are transparent and traceable, datasets comply with strict ethical and privacy standards, and humans remain integrated into the process – have slowed government’s ability to innovate at speed. In response to these perceived government failures, the decision is made to partner with industry to access the leading foundational AI models developed in the United States, Japan and the EU. The private companies utilise their powerful AI models to collect data and match users to public services and obligations. The government covers the cost of public service delivery with public funds.

Australians are provided options regarding which service provider they prefer for the delivery of public services. Organisations such as GoogelSoft and Sonitendo offer a premium, highly personalised service using what is marketed as ‘free-range data’. Clients must purchase brand computers, phones, watches and other wearables, which constantly collect data, such as location, purchases, internet searches, health statistics, contacts, calendars and even mood. The data is collected as clients ‘roam free’, building a highly detailed user-profile to inform which public services would best suit the client and how they are best delivered.

Service quality and personalisation are of a high standard for those on free-range data plans. However, clients have little control over how their data is used, which countries it is stored in, and reports suggest that commercial services (such as health insurance, airlines and premium streaming platforms) will soon be able to use client data to pitch highly personalised services to clients on these platforms ostensibly designed for public service delivery.

Other private providers such as MetaProvide and Seimenservice utilise democra-data (anonymised and encrypted data aggregated across matching indicators such as age, income, gender and location), and ethical data (government data sets stored onshore and subject to strict standards and monitoring). Clients are not required to purchase branded devices and need only provide minimal personal information, much the same as what is needed when opening a bank account or purchasing life insurance. All costs involved with the plan are covered by public funding.

Those on democra-data and ethical plans do not enjoy high levels of personalised service like those on the premium free-range plans. However, services are predictable, reliable and provide a level of security and privacy with the knowledge that their data is regulated and protected under a government they can access and hold to account.

The Public private partnerships scenario sought to:

- Have participants consider a future where private industry-owned AI models are integrated into the delivery of public services. This tested sensitivities of personal data being in the hands of private industry, and test sensitivities regarding the potential for personal data to travel outside of Australia’s jurisdiction.

- Drive discussion around the differing levels of sensitivity in providing personal data across differing societal cohorts.

- Have participants consider the fairness of varying levels of public service delivery and discuss the influence on Australian society when people share differing experiences in what kind of services they receive as a citizen or resident of the one country.

The scenario workshop identified that people:

- Want agency and control about the level of personal data they provide.

- Are concerned about equity, access to services, and privacy, and that being unwilling to share data may lead to some groups being excluded from the benefits offered by this scenario.

- Are reluctant to share data with private companies and do not trust that private companies would only use the data collected for the stated purposes.

- Consider that foundational AI solutions should be developed in-house, or, at the very least, that corporations should be held to the same standards as government.

- Are sensitive around the security of personal data, how it may be used by future governments and if personal data would be stored outside of Australia's jurisdiction.

Concluding comments

Participants in the workshop engaged generously with these scenarios. The discussions were lively and robust and participants allowed themselves to ‘feel’ and ‘think’ about what it might be like to be part of the potential future, and to share their thoughts on how they or others might be affected and might respond in such a future.

The Long-term Insights Briefing project team would like to acknowledge and thank all participants of the various focus groups, workshops and engagements that were held as part of the development of the briefing.

Back to topAppendix A: Who we spoke to

Community organisations

- Office for Women SA

- YWCA Australia

- Federation of Ethnic Communities Council of Australia

- Community First Development

- National Women’s Safety Alliance

- Equality Rights Alliance

- Harmony Alliance

- The National Rural Women’s Coalition

- Women with Disabilities Australia

- National Older Women’s Network

- National Employment Services Association

- St Vincent de Paul Society

- InDigital

- Department of Veterans Affairs (representing veterans voices)

- Australian Healthcare and Hospital Association

Academia/Industry/Youth

- Australian Medical Association

- Amazon Web Services

- ANU – School of Computing, College of Arts and Social Sciences, College of Science, College of Law

- ANU - Youth

- The Gradient Institute

- National AI Centre

- Australian Information Industry Association

- IBM

- University of Technology Sydney – Human Technology Institute

Australian Public Service

- Department of Industry, Science and Resources

- Digital Transformation Agency

- CSIRO/Data 61

- Office of the Chief Scientist

- National Disability Insurance Agency

- Australian Taxation Office

- Department of Home Affairs

- Department of Veterans Affairs

- Services Australia

- IP Australia

- Treasury

- Australian Public Service Commission

- Department of Employment and Workplace Relations

- Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade

- Productivity Commission

- Australian Border Force

- Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (2022), Trust in Australian public services: 2022 Annual ReportReturn to footnote 1 ↩

- National Skills Commission, State of Australia’s Skills 2021: now and into the futureReturn to footnote 2 ↩